Nationally, only about 68,000 people on average earned the federal minimum wage in the first seven months of 2023, according to a New York Times analysis of government data. That is less than one of every 1,000 hourly workers. Walmart, once noted for its rock-bottom wages, pays workers at least $14 an hour, even where it can legally pay roughly half that.

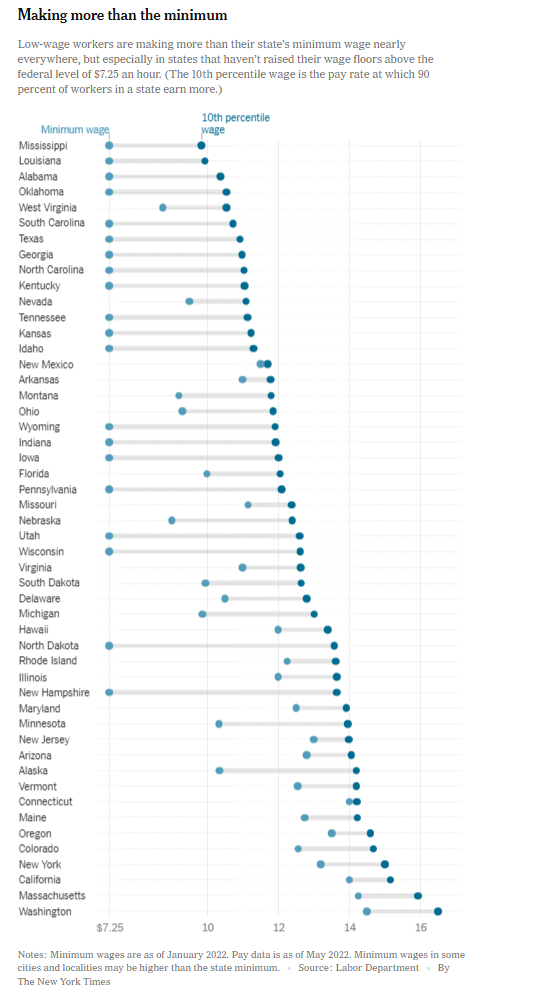

There are still places where the minimum wage has teeth. Thirty states, along with dozens of cities and other local jurisdictions, have set minimums above the federal mark, in some cases linking them to inflation to help ensure that pay keeps up with the cost of living.

But even there, most workers earn more than the legal minimum.

“The minimum wage is almost irrelevant,” said Robert Branca, who owns nearly three dozen Dunkin’ Donuts stores in Massachusetts, where the minimum is $15. “I have to pay what I have to pay.”

As a result, the minimum wage has faded from the economic policy debate. President Biden, who tried and failed to pass a $15 minimum wage during his first year in office, now rarely mentions it, although he has made the economy the centerpiece of his re-election effort. The Service Employees International Union, which helped found the Fight for $15 movement more than a decade ago, has shifted its focus to other policy levers, though it continues to support higher minimum wages.

Opponents, too, seem to have moved on: When Pennsylvania’s House of Representatives voted this year to raise the state’s $7.25 minimum wage to $15 by 2026, businesses, at least aside from seasonal industries in rural areas, shrugged. (The measure has stalled in the state’s Republican-controlled Senate.)

“Our members are not concerned,” said Ben Fileccia, a senior vice president at the Pennsylvania Restaurant and Lodging Association. “I have not heard about anybody being paid minimum wage in a very long time.”

The question is what will happen when the labor market cools. In inflation-adjusted terms, the federal minimum is worth less than at any time since 1949. That means that workers in states like Pennsylvania and New Hampshire could struggle to hold on to their recent gains if employers regain leverage.

Congress hasn’t voted to raise the minimum wage since George W. Bush was president ・in 2007, he signed a law to bring the floor to $7.25 by 2009. It remains there 14 years later, the longest period without an increase since the nationwide minimum was established in 1938.

As the federal minimum flatlined, however, the Fight for $15 campaign was succeeding at the state and local levels. Cities like Seattle and San Francisco adopted a $15 minimum wage, followed by states like New York and Massachusetts. And while Republican legislatures opposed raising minimums, voters often overruled them: Missouri, Florida, Arkansas and other Republican-dominated states have passed increases through ballot measures in the past decade.

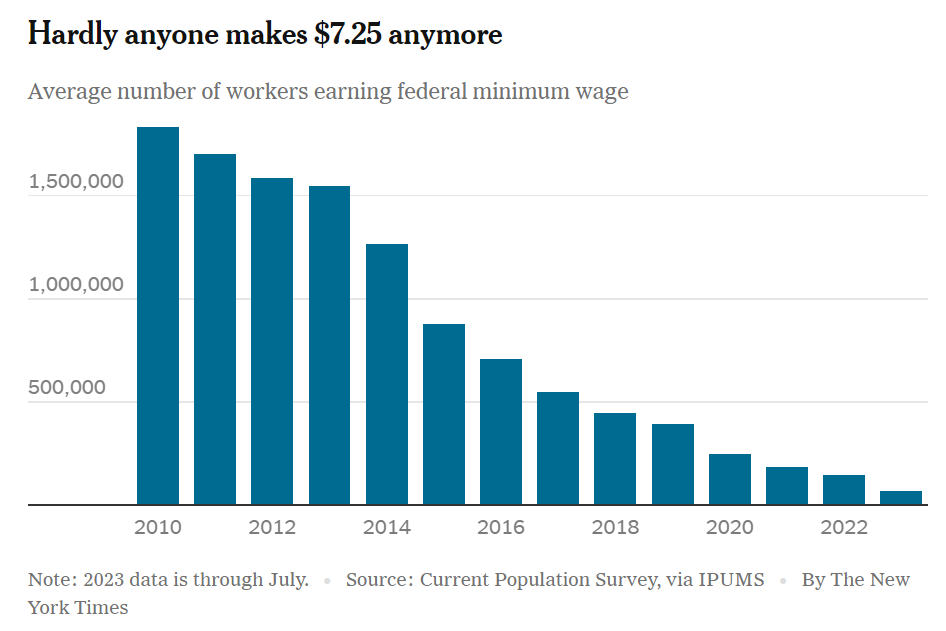

Nationwide, the number of people earning the minimum wage fell steadily, from nearly two million when the $7.25 floor took effect to about 400,000 in 2019. (Those figures omit people earning less than the minimum wage, which can in some cases include teenagers, people with certain disabilities or tipped workers.)

Then Covid-19 upended the low-wage labor market. Millions of cooks, waiters, hotel housekeepers and retail workers lost their jobs; those who stayed on as “essential workers” often received hazard pay or bonuses. As businesses began to reopen in 2020 and 2021, demand for goods and services rebounded much faster than the supply of workers to deliver them. That left companies scrambling for employees ・and gave workers rare leverage.

The result was a labor market increasingly untethered to the official minimum wage. In New Hampshire, the 10th percentile wage ・the level at which 90 percent of workers earn more ・was just above $10 in May 2019. By May 2022, that figure had jumped to $13.64, and local business owners say it has continued to rise.

“Today you’re looking at $15 an hour and saying I wish that’s all we had to pay,” said David Bellman, who owns a jewelry store in Manchester, N.H.